The skies are not always clear and blue in freelance Claudialand. If you want or *need* any writing, please feel free to email me. You can even use my favorite phrase from artlandia, “we need some words on that” or the even better “can I get some words on that?”

xoxo

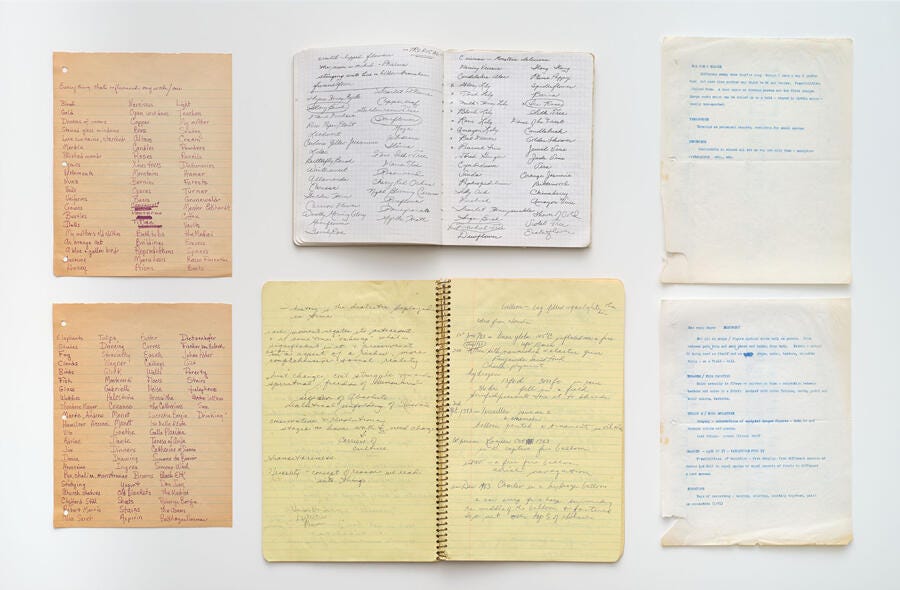

Rosemary Mayer at Marc Selwyn Fine Art and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles

In my only recurring dream, I find new rooms hidden within my apartment. Two simultaneous feelings accompany their discovery: sadness that I had not noticed them earlier, and excitement at the prospect of what they might offer. My viewing of Rosemary Mayer’s two-gallery retrospective, ‘Noon Has no Shadows’, held jointly at Marc Selwyn Fine Art and Hannah Hoffman Gallery, evoked similar sensations. ‘Dreams of rooms’ are, in fact, among the many items and ideas that Mayer names in a handwritten list on display at Hoffman, Everything That’s Influenced My Work / Me (c.1978): ‘Bernini’, ‘poverty’ and ‘aspirin’ also appear in the artist’s scrawl. This irreverent admixture is characteristic of Mayer’s oeuvre, which frequently combines canonical art forms with quotidian materials and expressions of social conviction. Proposals for public monuments and housing, rendered in colourful illustration and handwritten text, are plentiful; elsewhere, drawings pair depictions of expensive antiques with urgent pleas for cash. Including a number of previously unseen works, Mayer’s posthumous Los Angeles debut is both playful and political.

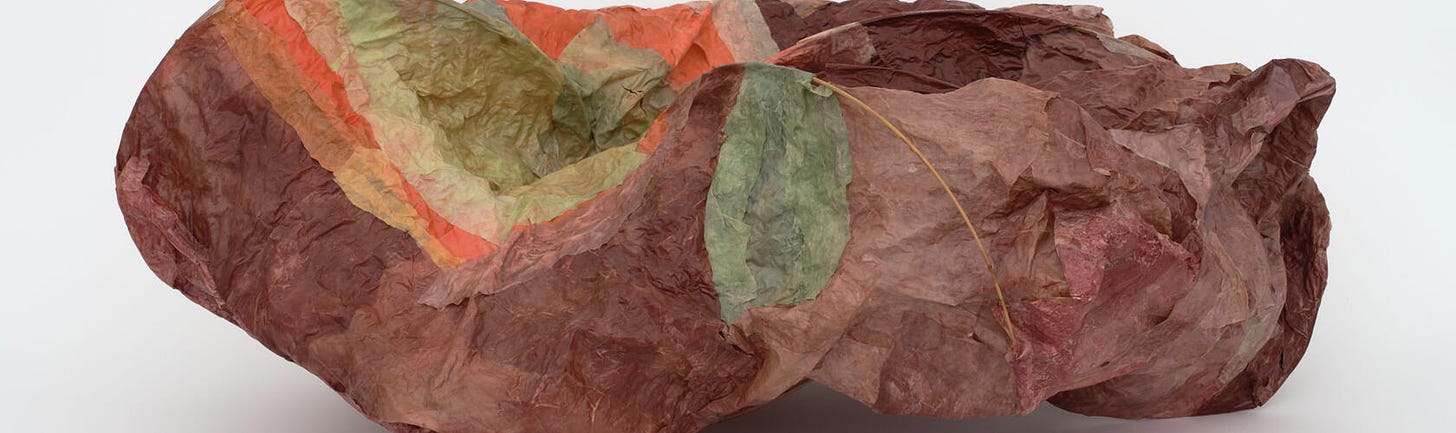

A focus on accessibility and social change infuses Mayer’s whimsical aesthetic. In the small watercolour sketch City Roof Tent on Wheels (1980), an ad hoc shelter resembling a festive May Day gazebo appears mid-movement, sliding down a set of city steps. Jane’s Moon Tent (1978) features a similarly cheerful hut with the emphatic phrase ‘anyone could make one’ jotted below it. Accompanying sculptures at Selwyn appear as the provisional, physical manifestation of these propositions: Vase Caravel (1984), for instance, stretches beige rag vellum across a wooden armature to form a structure that resembles, as the title suggests, both a sailboat and a water vessel – one that could either shield or serve its user. These pieces propose – and momentarily fulfil – solutions to pressing civic questions; Mayer’s artwork occupies the fragile, illusory space between fantastical vision and activist claim.

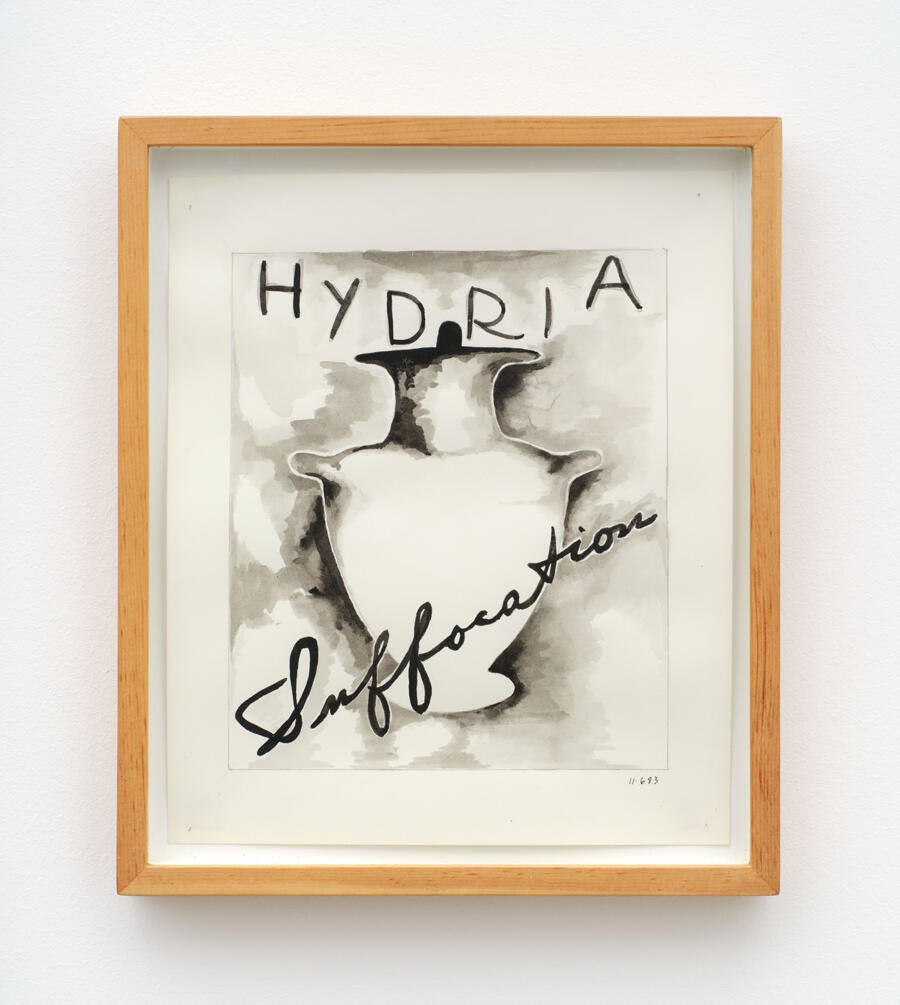

Playful winks at venerated objects animate Mayer’s appeals for social change. The enormous Portae (1980–81/2023) floats across a room at Hoffman, its bridge-like structure draped in grey, yellow and red fabric. The piece implies both a portae – an antiquated, luxury wine cradle – and an arched opening or portal to another, perhaps better, world. Nearby works on paper detail Mayer’s professional struggles in text overlaid on delicate drawings: the titular phrase in ICY DARK BROKE (1983) sits atop a bouquet of blooming lilies and daffodils while in NO MORE MONEY (1983) it accompanies a coloured-pencil rendering of a starfish. The latter artwork appears to be both an artistic elaboration of Mayer’s personal condition (in her 1971 journals, discussions centre on a lack of consistent income) and a call for the abolition of painful financial structures. Mayer evokes shared cultural pasts that creep into the present: depictions of Classical Greek vases at Selwyn sit alongside words such as ‘HUNGER’ and ‘SUFFOCATION’ to hint at more revolutionary positions.

This past November, the Estate of Rosemary Mayer, which co-sponsored the exhibition, actualized one of Mayer’s unrealized proposals, detailed in a 1978 illustration on view at Selwyn. Connections Los Angeles (2023) invited five LA-based artists to dedicate balloons to loved ones before releasing them to float above the city at the Wallis Annenberg Center in Beverly Hills. Staying true to Mayer’s spirit, the artists hung bright ribbons and celebratory streamers from each balloon. Mayer, who passed away in 2014 aged 70, transgresses temporal boundaries easily: her socially oriented, inclusive projects dig into the past and surmise alternative futures. Meditations on time, politics and loss are not new to fine art, but Mayer’s work proves both enduring and engaging, equal parts cogent reflection and utopian dream.

Rosemary Mayer, ‘Noon Has No Shadows’, is on view at Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles, until 23 December.

Sable Elyse Smith at Regen Projects, Los Angeles

In the original version of the game knucklebones, or jacks, Ancient Greek children tossed a rock into the air and tried to pick up a set of scattered astragali – sheep’s ankle bones – before it fell. The modern iteration employs a set of six-pointed plastic jacks; two such objects appear in oversized, black-and-white form at Sable Elyse Smith’s recent exhibition, ‘FAIR GROUNDS’, at Regen Projects in Los Angeles. These twin sculptures, entitled BARRIER and BARRICADE (all works 2023), are formed from conjoined prison stools, revealing the specificity of jail-oriented design – they are backless to increase inmate visibility – and hinting at the sinister side of entertainment. Smith’s multimedia artworks transform the detritus of the carceral state into contemporary spectacle, exploring the ways the American legal system morphs oppression into arcade.

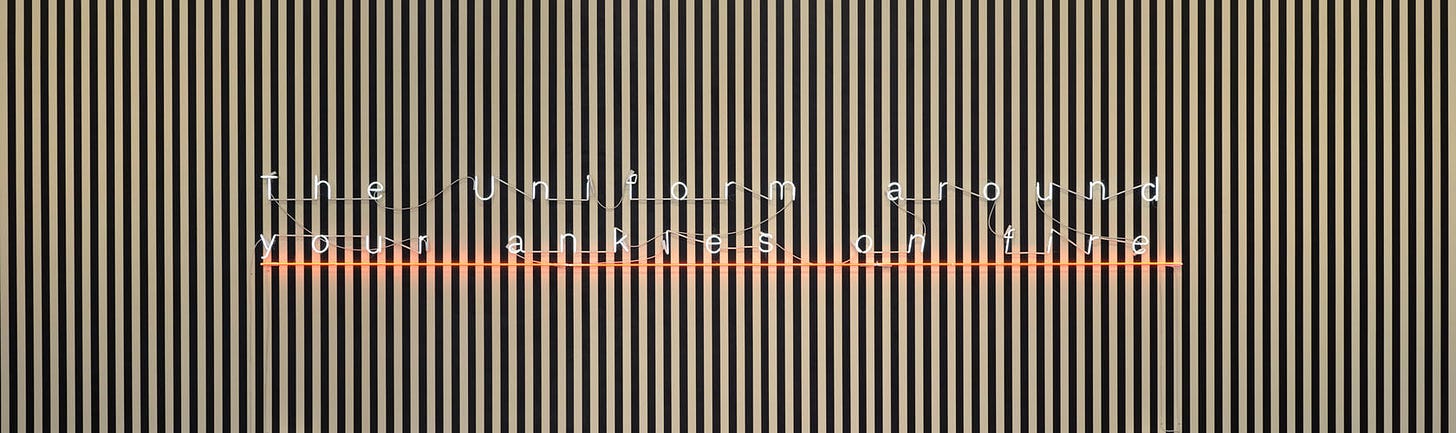

The exhibition title contains an apt double meaning: ‘fair grounds’ alludes both to the enclosed site of a state fair and to the basis upon which a person might justly be put on trial. Carnivals and penitentiaries emphasize their unique social functions through architecture; Smith employs visual signifiers of prison life to warp the viewer’s perceptions of depth and size, much like circus tents do to encourage a sense of gleeful exception. Black-and-white stripes that recall the metal bars of cells extend the length of four walls, producing a disorienting optical illusion: the lines appear to wave and bend, the gallery alternately shrinking or expanding. This transportive, theatrical backdrop finds another carceral corollary in three adjacent photographic works, such as 9861 Nights, that repurpose snapshots of family members posing with inmates in front of scenic dioramas during jail visitation days.

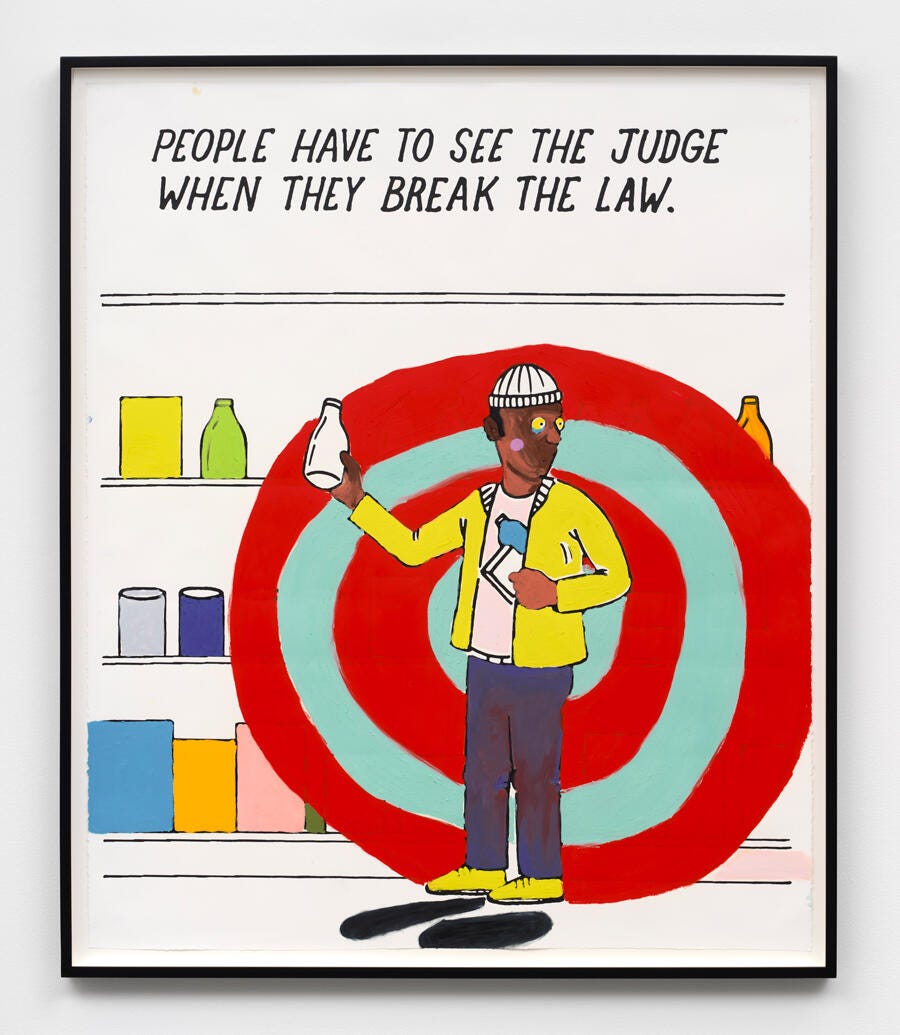

The double entendre extends to Smith’s adaptations of children’s media, transforming educational narratives about the law into carnivalesque depictions of the justice system. One series adapts pages from a colouring book meant to explain the judicial process to kids; in Coloring Book 139, the sentences ‘ALL TYPES OF PEOPLE ARE JUDGES. THE ONLY IMPORTANT THING IS THAT THEY ARE FAIR AND HONEST’ appears next to three figures painted over to resemble clowns and ringmasters. Smith’s interventions wryly hint at police brutality, a facet of criminal persecution hidden in her source material: Coloring Book 135 shows a figure grabbing a bottle from a shelf in front of a painted bright red-and-blue target, his abdomen at the bullseye’s centre. Elsewhere, a short video, all-together-now, layers a clip from the cartoon Tom and Jerry (1940–present) over found footage of burning buildings along a darkened city street. Smith’s juxtaposition situates comic demonstrations of power (in this episode, as always, predator Tom hunts his wily prey) amongst its real consequences: the background video’s grainy quality and fiery scene recalls documentation from 2020’s nationwide protests following George Floyd’s murder by police. In Smith’s hands, the rigid structure of American law becomes a grotesque theatre, one that often masks the harm dispensed onto its subjects.

‘I’m saying “prison”,’ Smith wrote for her 2022 display at the Whitney Biennial, ‘and meaning “the world.”’ This conceptual twist is not just an artistic one: circuses, college preparatory schools and rehabilitative penitentiaries co-evolved in the US during the 19th century. The institutions share structural similarities: each offers a sequestered site intended to maximize reformative potential (in the circus, viewers were shown how not to behave) while isolating unassimilated individuals from society. Their design elements, too, appear surprisingly alike: the artist’s reconstructed stools have the rounded edges and small size of chairs found in day care centres. Smith’s renegotiations of material found in classrooms, cells and carnivals link these disparate locales, illuminating the complexity of narratives that construct and enact power in the United States. It’s hard not to imagine a large hand hovering over Regen Projects, waiting to snatch the ‘jacks’ – and us – right up.

Sable Elyse Smith, ‘Fair Grounds’, is on view at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, until 26 October.